Bull Horn Acquisition Corporation raised $75m in an initial public offering in November 2020. The company was a special purpose acquisition company that expected to use its extensive experience in sports to help it acquire a major league sports franchise, or a media or technology business closely tied to sports.

Instead, Bull Horn closed a deal with a company that uses chimeric antigen receptors (to kill cancer cells) two years later.

Bull Horn turned out to be one of the lucky ones, data shows that there are still 62 blank check companies in sports with capital-seeking deals totaling over $15.9 billion.

“Our ultimate goal was to create shareholder value and to create a merger with a company that returns value,” Bull Horn co-founder Rob Striar said. Three weeks ago Bull Horn closed a merger with Coeptis Therapeutics, a development-stage biopharmaceutical company focused on cell therapies for cancer patients.

“We are really happy with the deal, with the merger and their management team,” Striar said. “I don’t think it changes our belief that sports as an asset class would continue to grow and outpace many other assets and investments and that institutional money would flow into it.”

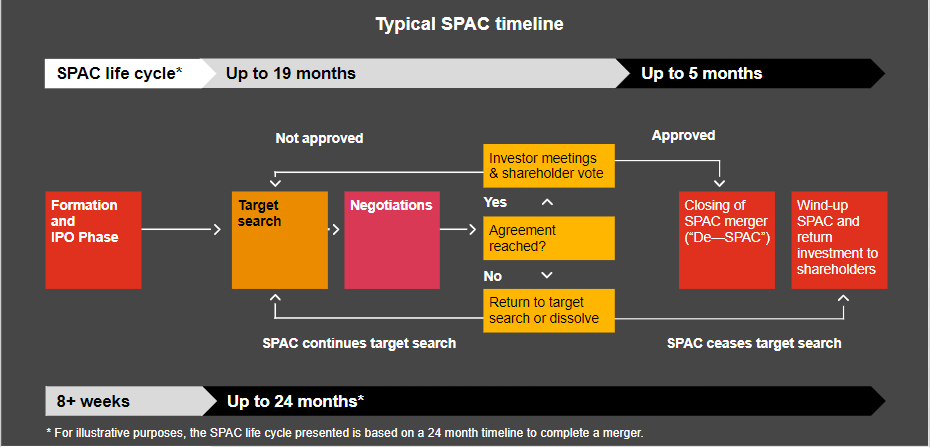

Bull Horn was a pioneer in the rise of SPACs. These are companies that raise capital in an IPO to find an operating business to go public.

Striar, who has been a part of M Style Marketing’s work with CONCACAF and the NHL, joined other sports experts like Baron Davis, Michael Gandler, owner of the Italian soccer team, and Stephen Master, former head for global sports at Nielsen.

SPACs cannot guarantee to find deals in all sectors, but most indicate preferred business types, like Bull Horn.

The stock market success of DraftKings SPAC merger in early 2020 sparked another 168 SPACs to form in less than 24 months. These SPACs had a connection with sports, either with a preference for sports or with an industry executive.

According to data, they were part of a group of 931 SPACs who held their IPOs in the last three years.

According to market participants, at the height of the frenzy teams from at least four top-tier leagues — MLB and the NBA — were considered going public by SPAC. This didn’t happen, evidently, as the stock market became bearish and inflation undercut the multiples investors were willing to pay for stocks.

Consequently, regulators cracked down upon SPACs. They warned investors about the dangers involved in investing because of the involvement of celebrities or athletes. Any deal, such as Bull Horn’s proposed merger with a French mobile payment firm by Goal acquisitions last week, is now an exception to the rule.

These are the results of the 168 SPACs in sports formed since 2020. There are some notable examples.

- Successfully closed a merger: 39

- Trying to close an announcement merger: 7

- Actively looking for a deal: 62

- Dissolution without finding a merger: 10

- Dissolution by year-end: 3

- Trying to price their IPO: 20

- Never held their IPO: 30

This tally shows that sports SPACs have a winning percentage of only 23%.

And it’s not looking any brighter.

A tax on share buybacks, which will be in effect at the beginning of 2023, will further increase the pressure on SPACs. This tax, which is a 1% levy per transaction, was introduced by the federal Inflation Reduction Act.

SPACs will likely be subject to the tax due to the unique structure of SPACs, which return IPO capital to shareholders on demand or at a merger vote. Some blank check operators have attempted to close their doors by the end of the year to reduce their losses.

These include Athlon Acquisition, which is led by Mark Wan, Celtics co-owner; media- and sports-focused Argus Capital; billionaire Ken Moelis’ sports betting-focused Atlas Crest II.

Despite these difficulties, many active sports SPACs have $15.9bn in IPO capital. The notable names still operating the phones are Arctos NorthStar and Alex Rodriguez’s Slam Corporation. Also, Disruptive Acquisition II has the participation of Naomi Osaka and Robert Lewandowski.

According to data, 40 active sports SPACs have deadlines for closing mergers. These deadlines fall within the first six months in 2023 and takes around four months for a deal to be finalized.

SPACs are able to get shareholders to approve an extension like Bull Horn, but it is not guaranteed. Shareholders can request the IPO capital back at voting, which many do.

Participants remain positive that these vehicles will continue to be used in the future, regardless of how successful the SPACs may be in the short term.

Ritter stated that they will likely choose a form that is less lucrative for SPAC sponsors who get returns from the dirt-cheap warrants they use to purchase shares in the resulting company.

Ritter stated that a sponsor must make concessions and put in extra money to ensure the deal does not collapse. “Those are market forces, the sponsor is giving away a portion of their pie because they have been given too much.”

Striar said that the absence of SPAC mergers in culminated sports should not be taken to mean there is no market interest.

He said that the most interesting thing for him was the amount of deal flow, and the creativity involved in the deal flow. It’s enabled us to talk to other investment groups who want to partner with us.

Now that the deal is done, it’s been possible to contact other SPACs. Institutional money is still coming.”

Lots of dry powder on the sidelines in sports.